The origins

A history etched in marble

The story of Forte dei Marmi begins with a road. As early as the 15th century, Via di Marina linked the mountainous hinterland to a small landing point along the coast, between the Torre del Cinquale and the Fortezza di Motrone, then a thriving maritime hub. This route was essential for transporting precious marble from the Apuan Alps to the sea, marble personally selected by masters such as Michelangelo Buonarroti and Giambologna.

As marble trade expanded in the early 16th century, a new road toward the coast was laid out. Before reaching the beach, it crossed the Versilia plain, at the time uninhabited, heavily wooded, but also marshy, unhealthy, and frequently targeted by pirates. The construction of this new route, today’s Via Provinciale, was commissioned by Pope Leo X of the Medici family and carried out by sculptor Donato Benti, a collaborator of Michelangelo Buonarroti. Inaugurated in 1518, the road soon became vital not only for marble transport but also for the iron trade from the island of Elba, processed in local Versilia foundries. The coastal warehouse built for this commerce still stands today on Via Duca d’Aosta.

A major turning point came at the end of the 18th century, when the Medici dynasty ended, and the House of Habsburg-Lorraine became the Grand Dukes of Tuscany. The new rulers of these lands immediately undertook ambitious land-improvement projects, reclaiming marshes and restoring the coastal pinewoods. It was Grand Duke Leopold I who commissioned the construction of the Fortino, still the defining symbol of Forte dei Marmi, as both a military and commercial stronghold. Built between 1785 and 1788, the structure reflected the needs of its time: compact, multifunctional, and designed to meet military, customs, and public-health requirements.

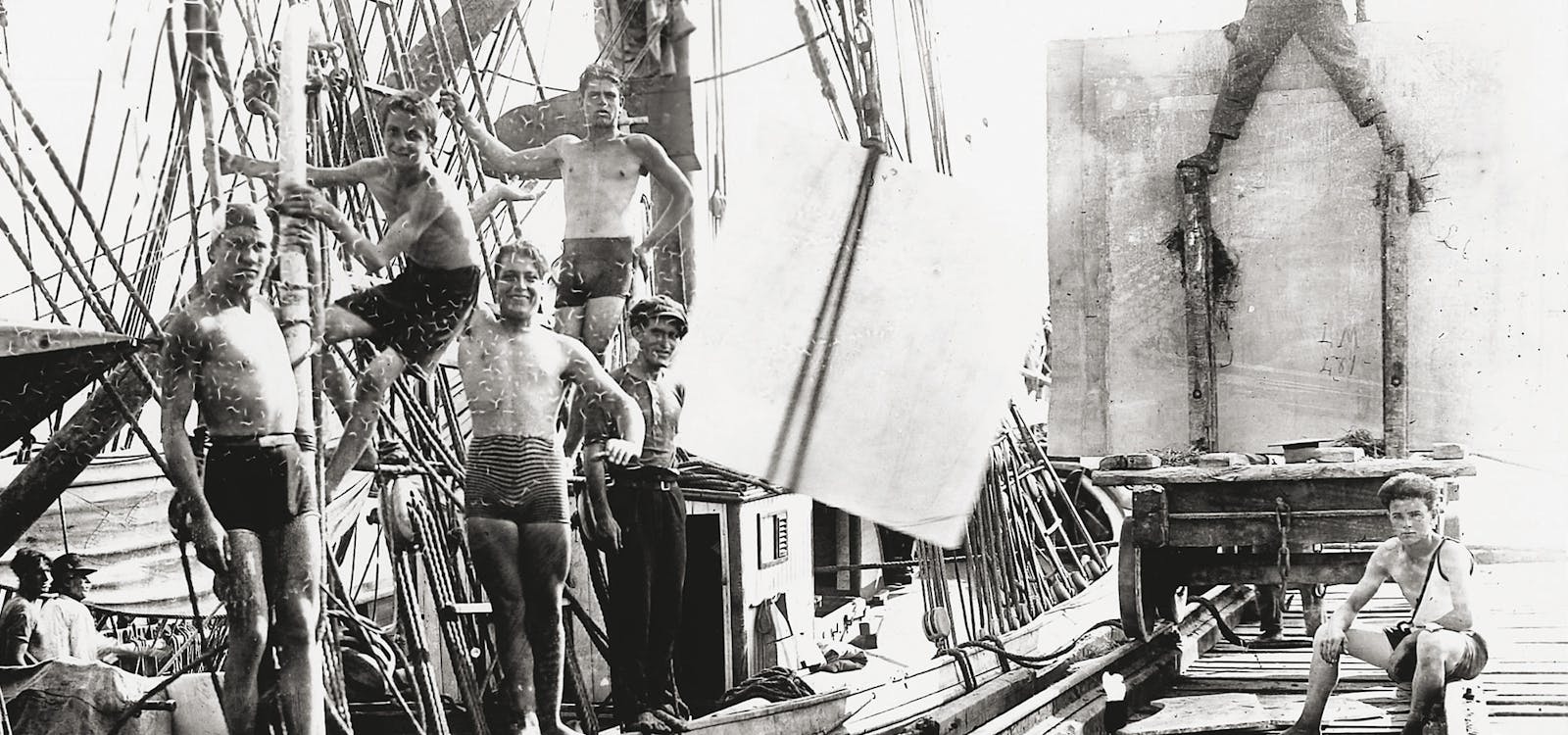

In the early 1800s, the first homes began to appear. Forte dei Marmi, then a small settlement under the jurisdiction of Pietrasanta, became the strategic maritime outlet for marble exports on which much of the territory depended. Growing commercial activity, now including foodstuffs and various goods, made it necessary to restore Via Nuova di Marina. Goods were transported by ox-drawn carts to the shore and loaded onto boats using barges or by hauling vessels directly onto the sand. As trade intensified, so did population growth: by 1822, the village counted around 300 inhabitants, most of them connected to the maritime work.

Between 1876 and 1877, engineer Costantini designed and constructed the iconic pier to enhance port operations. It was equipped with a crane known as La Mancina, which significantly boosted docking and loading efficiency. Meanwhile, the town continued to grow with the granting of land around and near the Fortino. The Church of Sant’Ermete was built during the same period to serve the village's residents. In 1907, the arrival of the steam train further strengthened connections for both people and goods.

While marble trade defined the birth and early growth of Forte dei Marmi, its rise as a seaside resort came much later. In the 19th century, the Tyrrhenian coast was famous for Viareggio, which was already fashionable, but those seeking peace and discretion chose Forte dei Marmi for sea bathing and heliotherapy. Wealthy families and tourists began building elegant villas nestled in the pine woods in what is now the Roma Imperiale district.

In a short time, Forte dei Marmi became one of the Mediterranean’s most sought-after destinations, prized for its crystal-clear waters, high quality of life, lush gardens, pristine greenery, and the dramatic proximity of the Apuan Alps. Italian and international figures arrived, politicians, industrial leaders, European nobility, alongside artists and intellectuals such as Dazzi, Carrà, Carena, Soffici, Gentile, Pea, and Viani. They gathered at the Caffè Quarto Platano on Piazza del Fortino, exchanging ideas and shaping cultural and artistic debates of the time. Carlo Carrà, who spent long periods here, captured glimpses and landscapes of Forte dei Marmi in a series of paintings that remain a testament to his profound bond with the town.

The year 1914 marked another milestone: Forte dei Marmi separated from the Municipality of Pietrasanta and became an independent town. A lasting symbol of this shared history remains in the central fountain of Piazza Garibaldi, which still bears Pietrasanta’s coat of arms.